The ambitious Opera Manhattan Repertory Theatre is filling this weekend with a triple bill of dramas for "women on the verge." The project pairs two shorter works of Thomas Pasatieri--his 2007 song cycle Lady Macbeth, and 1980 monodrama Before Breakfast--with Francis Poulenc's La Voix Humaine. As well as being seasonally appropriate (for those who are, like myself, heartily fed up with foil-wrapped chocolates and paper sentiments for February 14th) the program was musically rich, and emotionally devastating.

I am more familiar with the text of each of the works presented than with the musical settings created for them. The insinuating melodies of Lady Macbeth, sensual and almost jazzy, had me considering Shakespeare's well-known words from a new angle. Sofia Dimitrova created a portrayal of a woman trapped in an unbearable situation, for whom power is an aphrodisiac. Pasatieri subverts "Ye ministers of night, unsex me here" with unmistakably sexy music, which echoes throughout the remainder of the songs, even as Lady Macbeth descends into madness, fighting all the way. Dimitrova's plush, rounded soprano embraced the eroticism of Lady Macbeth's daring the powers of hell and earth to stop her, balanced between confidence and desperation. Even in fixation on her guilt ("All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand") it is far from certain that she is not, still, aroused by the promise of greater freedom implicit in the metallic, vital smell of blood.

The second Pasatieri piece on the program was based on Eugene O'Neill's bleak Before Breakfast, but expanded to include more of the unnamed woman's history, and more of her mental disintegration. I missed O'Neill's savage refusal of sentimentality, but Meredith Buchholtz charted her persona's nostalgia and disillusion without overindulgent effects. Pasatieri's music sets both vivid memory (in carefree waltzes and desperate dance marathons) and the faded present, with the faint clink of crockery and the fainter dripping of blood. Buchholtz demonstrated both thoughtfulness with the text, and a fine sense for musical phrasing; her soprano was distinctive and expressive.

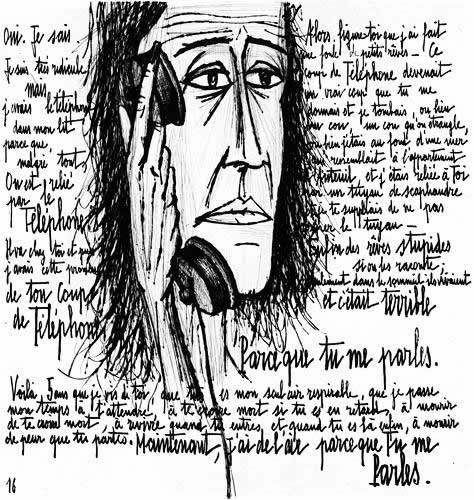

After the interval (which was, as predicted by producer David Browning, needed for emotional recovery) we had Poulenc. (Those who like messy despair paired with film noir sensibilities, check out this film with Denise Duval as Elle.) Of the play on which the opera is based, playwright Jean Cocteau said that it was an "unaesthetic act, a demonstration against aesthetes and snobs, against the young (who are the worst snobs of all,) capable of moving only those who are not expecting anything and who are without prejudice." I'm not sure if Poulenc's work has become too famous to vitiate these remarks, but I was moved, and many of those around me were visibly so as well. Even without orchestra, the immediacy of Poulenc's music made this most artificial of scenarios ring emotionally true. Indeed, it should be mentioned that pianist Tristan Cano provided sensitive partnership to each of the singers. Kala Maxym handled the demands of the text, as well as those of the vocal line, well (although there were projected surtitles, it was nice to be independent of them.) Her "Elle" had a fearful kind of dignity, even at her most frantic. The warmth of Maxym's soprano conveyed a tenderness more terrifying than fury, as she assures the man on the other end of the line that she is strong, and calm, and above all truthful. The final confession, "Je t'aime," is of course, in a sense, redundant; the whole conversation has said nothing else so clearly. But coming at the end of such an involving performance, it came as what Evelyn Waugh called "a blow expected, repeated, falling on a bruise, with no smart or shock of surprise, only a dull sickening sensation and the doubt whether another like it could be borne."

Sunday evening will see another cast charting these desperate emotional journeys.

|

| Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth |

The second Pasatieri piece on the program was based on Eugene O'Neill's bleak Before Breakfast, but expanded to include more of the unnamed woman's history, and more of her mental disintegration. I missed O'Neill's savage refusal of sentimentality, but Meredith Buchholtz charted her persona's nostalgia and disillusion without overindulgent effects. Pasatieri's music sets both vivid memory (in carefree waltzes and desperate dance marathons) and the faded present, with the faint clink of crockery and the fainter dripping of blood. Buchholtz demonstrated both thoughtfulness with the text, and a fine sense for musical phrasing; her soprano was distinctive and expressive.

After the interval (which was, as predicted by producer David Browning, needed for emotional recovery) we had Poulenc. (Those who like messy despair paired with film noir sensibilities, check out this film with Denise Duval as Elle.) Of the play on which the opera is based, playwright Jean Cocteau said that it was an "unaesthetic act, a demonstration against aesthetes and snobs, against the young (who are the worst snobs of all,) capable of moving only those who are not expecting anything and who are without prejudice." I'm not sure if Poulenc's work has become too famous to vitiate these remarks, but I was moved, and many of those around me were visibly so as well. Even without orchestra, the immediacy of Poulenc's music made this most artificial of scenarios ring emotionally true. Indeed, it should be mentioned that pianist Tristan Cano provided sensitive partnership to each of the singers. Kala Maxym handled the demands of the text, as well as those of the vocal line, well (although there were projected surtitles, it was nice to be independent of them.) Her "Elle" had a fearful kind of dignity, even at her most frantic. The warmth of Maxym's soprano conveyed a tenderness more terrifying than fury, as she assures the man on the other end of the line that she is strong, and calm, and above all truthful. The final confession, "Je t'aime," is of course, in a sense, redundant; the whole conversation has said nothing else so clearly. But coming at the end of such an involving performance, it came as what Evelyn Waugh called "a blow expected, repeated, falling on a bruise, with no smart or shock of surprise, only a dull sickening sensation and the doubt whether another like it could be borne."

Sunday evening will see another cast charting these desperate emotional journeys.

I've always been curious about Lady Macbeth, and how much she wanted power. I'm going to look up this song cycle.

ReplyDeleteAll this sounds like a powerful antidote to Valentine's Day! :)