On Saturday, I headed downtown for the penultimate performance of Gounod's Faust, which filled Amore Opera's spring repertory staple slot this year. A fine orchestral performance, and impressively cohesive work from the chorus, supported a strong cast: a very creditable all-around effort. Director Nathan Hull used Amore's limited stable of sets intelligently, creating a staging that juxtaposed Gounod's era and the way that era imagined the opera's ostensible setting. Sixteenth-century urban spaces (looking strangely normal to anyone who's seen F.W. Murnau's amazing film of the story) surrounded townsfolk in mid-nineteenth-century garb, or approximations thereof. This is a strategy that has enjoyed a recent vogue in larger houses, and for Faust, I think it works: the passage of time is, obviously, Faust's main personal worry. In Goethe (cf. this post,) mutability on a larger scale is also a pressing, even torturing preoccupation for many: what good are new forms of knowledge if they don't alleviate human suffering? How do we explain--and counteract--evil if, in a rapidly secularizing society, we can no longer attribute it to diabolic agency? In Hull's production, Marguerite, like Faust, is fascinated by new knowledge and new ways of acquiring knowledge. She occupies her hours of petit bourgeois leisure with a stereoscope, approximating Faust's research and Valentin's travel in the only way allowed to her. Both this and the choreography suggested that the philosopher and the siblings are all the victims of Mephistopheles: a Mephistopheles who is part Caligari

of the story) surrounded townsfolk in mid-nineteenth-century garb, or approximations thereof. This is a strategy that has enjoyed a recent vogue in larger houses, and for Faust, I think it works: the passage of time is, obviously, Faust's main personal worry. In Goethe (cf. this post,) mutability on a larger scale is also a pressing, even torturing preoccupation for many: what good are new forms of knowledge if they don't alleviate human suffering? How do we explain--and counteract--evil if, in a rapidly secularizing society, we can no longer attribute it to diabolic agency? In Hull's production, Marguerite, like Faust, is fascinated by new knowledge and new ways of acquiring knowledge. She occupies her hours of petit bourgeois leisure with a stereoscope, approximating Faust's research and Valentin's travel in the only way allowed to her. Both this and the choreography suggested that the philosopher and the siblings are all the victims of Mephistopheles: a Mephistopheles who is part Caligari , part Dracula, and completely depraved. (As his power grows, his makeup becomes increasingly diabolical; there are visual echoes of Conrad Veidt's deformed hero in The Man Who Laughs

, part Dracula, and completely depraved. (As his power grows, his makeup becomes increasingly diabolical; there are visual echoes of Conrad Veidt's deformed hero in The Man Who Laughs . Mephistopheles' costumes and spotlights may be the kind of thing Bernard Shaw famously complained of, but as Goethe's devil remarks, turning Satan into a pantomime terror doesn't rid the world of evil's threat. Often, all Mephistopheles has to do is lurk in the background; the opera's human beings don't need much help damaging each other.

. Mephistopheles' costumes and spotlights may be the kind of thing Bernard Shaw famously complained of, but as Goethe's devil remarks, turning Satan into a pantomime terror doesn't rid the world of evil's threat. Often, all Mephistopheles has to do is lurk in the background; the opera's human beings don't need much help damaging each other.

Tuesday, May 28, 2013

Sunday, May 26, 2013

InsightALT Festival: New opera from sketchpad to stage

Thursday, May 23, 2013

Dialogues des Carmelites: il ne reste que l'Agneau de Dieu

I went to the last performance (of only three!) of the run of Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmelites which closed out the Met's season. The production and orchestra were solid, but it was the vocal performances that gave the evening its intellectual and emotional intensity. John Dexter's classic production is strong and stark, though it's hard for me to put myself in the place of audiences who saw it as revolutionary. Before the opening bars of the score are heard, we see the nuns all prostrate in the cruciform position. The grille, the rood screen, the prison bars all descend, making effective minimalist surroundings for naturalistic presentation. I quite liked the airy form of the grille, the incorporation of the cross into its pattern, emphasizing the voluntary rather than the absolute nature of the nuns' enclosure. The stage is marked--defined--by an ever-present cross. Its shape is obscured only at a handful of moments: it is in shadow while Blanche is in her father's house, cut off by the library with its Fragonard-like painting. Again it is partially hidden during the prioress' death scene, though she is in its light. During the martyrdom, the crowds mill in the transept, blind to it. I really liked this use of space suggesting the form of grace, the force of it even (especially?) in the mundane.

Sunday, May 19, 2013

Fin-de-siècle fantasies: Renee Fleming, Jeremy Denk, & the Emerson Quartet

|

| Adele Bloch-Bauer I: Gustav Klimt, 1907 |

Labels:

Brahms,

Carnegie Hall,

Renée Fleming,

Richard Strauss,

Schoenberg,

Wagner

Sunday, May 5, 2013

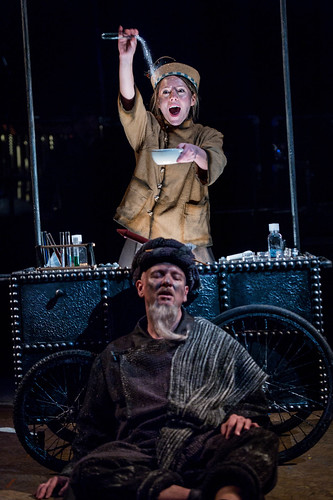

Nights like these: Firework-Maker's Daughter

|

| Joy of discovery: Bevan and Pencarreg in The Firework-Maker's Daughter |

Friday, May 3, 2013

Fin ch'han dal vino: Don Giovanni with the New York Opera Exchange

|

| Don Giovanni in 1963 |

The orchestra was a newly formed ensemble, and showed considerably improved cohesion over last year's showing, although there were issues in coordination with the singers. This I'm inclined to attribute to the inflexibility of conductor David Leibowitz's tempi. Balance issues in the first act were largely corrected in the second. The strings were occasionally imprecise but acquitted themselves well; the woodwinds performed with some distinction. The horns did well until the final scene, when disaster struck: the Commendatore was heralded with bizarre cacophonies. Fortunately, matters were set right for the final ensemble.

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Song of Norway: Grieg goes Broadway-style

|

| Danieley, Silber, and Fontana sing of Norway. Photo (c) Erin Baiano |

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

Ich sei das Weib! Goerke and the Greenwich Village Orchestra

|

| Christine Goerke. Photo via IMG Artists |

The Tannhäuser overture and bacchanal saw the orchestra at its finest, with each theme given dramatic value, and with sprightliness leavening the pseudo-medieval pomp and ceremony. When Goerke entered, she lit up the hall, embracing its dingy neoclassicism in an expression of radiant joy before launching into "Dich, teure Halle." Elisabeth's effervescent happiness filled Goerke's sound as her sound filled the hall. German nerd that I am, I loved the expression which Goerke gave to text. The very strength of her rich sound seemed almost to work against the desolation of "Allmächt'ge Jungfrau," but perhaps I have insufficient sympathy with Elisabeth's self-denying selflessness. Certainly Goerke sang it beautifully. I was delighted that the GVO gave this aria its response, Wolfram's achingly beautiful "O du mein holder Abendstern." Jesse Blumberg sang it with a resonant, warm baritone well-suited to it. I found myself wishing that the legato phrases had been taken more slowly, and that Blumberg's perfectly correct German had perhaps been invested with more poignancy, but judging by aufience response, these reservations placed me in a minority.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)