The progress of my summer reading list has been somewhat slowed by academic responsibility (alas) but I am currently immersed in Alexander Chee's recent The Queen of the Night, and it is so glorious that I can't wait for the eventual review to share it with you all. I got it from my local library, but it's the kind of book I'd love to own, the better to forcibly loan it to people, to say nothing of revisiting particularly lush passages of its gorgeous prose. It works (so far!) brilliantly well as a historical novel of the mid-nineteenth century, and is also a fascinating look at one woman's self-discovery... and discovery of opera. The evocation of opera in prose is, of course, a tricky thing. But it's also proved irresistibly tempting to many authors.... and bloggers. I was first drawn into the sphere of opera blogging because prose records of unique opera evenings were (and are) so much more numerous, and more accessible, than audio or visual records of them.

The dramatic use of opera in novels dates back at least to the Romantics, with Flaubert's Madame Bovary a justly famous example, and Dumas père's Le Comte de Monte-Cristo a less famous but equally fascinating one. (If you have favorite examples of opera evoked in prose, please share them!) I've been particularly intrigued by Chee's treatment of Il Trovatore, an opera he describes as "a tragedian's sleight-of-hand." The poignant ballad "Deserto sulla terra" he describes as perhaps the most beautiful song ever written for a man... which of course led me into a process of re-exploring the opera and this aria.

The earliest recording of the aria I could find dates to 1903. With its dedication to the father of tenor Francesco Tamagno, it functions as a curious double record: of the aria's enduring emotional power, and of changing tastes in performance. Attempting to reconstruct a rough chronology of Manricos, I next came to Gigli (having been balked of Caruso, for this aria.) I confess that Gigli's live performance of this was much more stirring to me, much more vocally and dramatically interesting. The live element helps; and despite the limitations of the recording technology, we still get a clear sense of the dynamic variation at play, of the use of text... even of the use of space, as singers pace away from the microphones and sections of music fall away from us. To me, this is one of the things recorded opera can best do: to give us some sense both of what it was like to hear and see it performed, and of all the richness we're missing by not doing so. Less than a decade later, in another live performance, Di Stefano would sing it like a challenge to the destiny Manrico battles. Similarly warlike is the remarkable Lauri Volpi.

My favorite Manrico is, perhaps unsurprisingly, Franco Corelli. This is partly because I am an absolute sucker for a performance style that defies the sensibilities of historically-bourgeois audiences and neglects restraint and propriety and even, sometimes, what is called "good taste," in favor of something much more important, something startling and passionate, something that is true, or at least dreams of being so. Corelli's performance of the aria at his Met debut can be heard here; I'm particularly fond of the 1962 Salzburg recording I own. The brutal--and admittedly capricious--quality filter of time, to say nothing of technology, means that the landscape of interpretations grows more crowded in more recent decades. Domingo's is yearningly beautiful, reminding me that I should revisit his early work more often. Marcelo Alvarez (my first live Manrico) sings it, interestingly, while emphasizing its qualities as a ballad, rather than its function as a cri de coeur. Roberto Alagna's interpretation, I think, strikes a balance between the aria's two identities. I can't think of a better way to conclude this selective survey, Gentle Readers, than to ask you about your own favorite Manricos, whether recorded, or translated into prose from your own memories of that irreplaceable experience that is live opera.

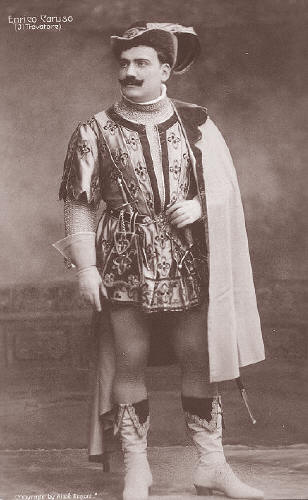

|

| Caruso as Manrico |

The earliest recording of the aria I could find dates to 1903. With its dedication to the father of tenor Francesco Tamagno, it functions as a curious double record: of the aria's enduring emotional power, and of changing tastes in performance. Attempting to reconstruct a rough chronology of Manricos, I next came to Gigli (having been balked of Caruso, for this aria.) I confess that Gigli's live performance of this was much more stirring to me, much more vocally and dramatically interesting. The live element helps; and despite the limitations of the recording technology, we still get a clear sense of the dynamic variation at play, of the use of text... even of the use of space, as singers pace away from the microphones and sections of music fall away from us. To me, this is one of the things recorded opera can best do: to give us some sense both of what it was like to hear and see it performed, and of all the richness we're missing by not doing so. Less than a decade later, in another live performance, Di Stefano would sing it like a challenge to the destiny Manrico battles. Similarly warlike is the remarkable Lauri Volpi.

My favorite Manrico is, perhaps unsurprisingly, Franco Corelli. This is partly because I am an absolute sucker for a performance style that defies the sensibilities of historically-bourgeois audiences and neglects restraint and propriety and even, sometimes, what is called "good taste," in favor of something much more important, something startling and passionate, something that is true, or at least dreams of being so. Corelli's performance of the aria at his Met debut can be heard here; I'm particularly fond of the 1962 Salzburg recording I own. The brutal--and admittedly capricious--quality filter of time, to say nothing of technology, means that the landscape of interpretations grows more crowded in more recent decades. Domingo's is yearningly beautiful, reminding me that I should revisit his early work more often. Marcelo Alvarez (my first live Manrico) sings it, interestingly, while emphasizing its qualities as a ballad, rather than its function as a cri de coeur. Roberto Alagna's interpretation, I think, strikes a balance between the aria's two identities. I can't think of a better way to conclude this selective survey, Gentle Readers, than to ask you about your own favorite Manricos, whether recorded, or translated into prose from your own memories of that irreplaceable experience that is live opera.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Start a conversation!