The calendar year is tapering quietly to its end; here in Mainz, the days are rainy and the archives are closed, providing ideal conditions for retrospection on a year of opera-going. I've already been enjoying the reports of others on the year in opera: John Gilks at Opera Ramblings, Mark Berry at Boulezian, and the anonymous Opera Traveller. My own year of opera has been an unusual one, divided as it has been between two continents. While I miss the sheer exuberant variety of NYC's opera scene, I have loved discovering the work of solid house ensembles in Mainz and Wiesbaden, and the consistent intelligence of Frankfurt's musically polished productions. So, without further ado, Gentle Readers, I present my entirely subjective roundup of favorite performances this year: ones that have afforded not only excellent nights at the opera, but lingering memories pleasurable and thought-provoking.

7 great nights:

Yes, I've expanded the category this year: five really great evenings, plus another one I didn't have the intellectual energy to review, plus a Parsifal in a class by itself. In reverse chronological order:

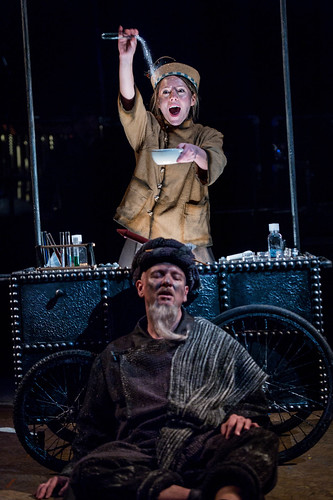

At Oper Frankfurt, Brigitte Fassbaender's new production of Ariadne auf Naxos proved intellectually stimulating and warmly humane, with humor and hints of mysticism that both served the work well. The orchestra shone, and the singers not only handled Strauss' music beautifully, but worked beautifully with each other as an ensemble. Also in Frankfurt, I witnessed the minor miracle of a non-sexist Tannhäuser production, with overwhelmingly gorgeous orchestral work (yes, I got teary,) and very fine Wagnerian singing. The Met's all-too-brief revival run of Dialogues des Carmelites was a perfect way to bid a (temporary) farewell to the house that's been my home base for the last five years. John Dexter's production remains striking and effective, the orchestra is of course brilliant, and the cast was truly superb. The Firework-Maker's Daughter was another highlight of my spring season. A children's opera, you ask, Gentle Readers? Yes: and an opera that used small forces creatively, is both humorous and poignant, critiques sexism in opera and society (hooray,) and boasts well-set text and memorable music. I am still unreconciled to the sad demise of New York City Opera. Its last spring programming was so good, and so well-received, that it seemed to promise happier days ahead. Thomas Adès' Powder Her Face--mordant and musically creative--was presented with a uniformly strong cast in a bold production. I'm very glad I got to see it.

7 great nights:

Yes, I've expanded the category this year: five really great evenings, plus another one I didn't have the intellectual energy to review, plus a Parsifal in a class by itself. In reverse chronological order:

At Oper Frankfurt, Brigitte Fassbaender's new production of Ariadne auf Naxos proved intellectually stimulating and warmly humane, with humor and hints of mysticism that both served the work well. The orchestra shone, and the singers not only handled Strauss' music beautifully, but worked beautifully with each other as an ensemble. Also in Frankfurt, I witnessed the minor miracle of a non-sexist Tannhäuser production, with overwhelmingly gorgeous orchestral work (yes, I got teary,) and very fine Wagnerian singing. The Met's all-too-brief revival run of Dialogues des Carmelites was a perfect way to bid a (temporary) farewell to the house that's been my home base for the last five years. John Dexter's production remains striking and effective, the orchestra is of course brilliant, and the cast was truly superb. The Firework-Maker's Daughter was another highlight of my spring season. A children's opera, you ask, Gentle Readers? Yes: and an opera that used small forces creatively, is both humorous and poignant, critiques sexism in opera and society (hooray,) and boasts well-set text and memorable music. I am still unreconciled to the sad demise of New York City Opera. Its last spring programming was so good, and so well-received, that it seemed to promise happier days ahead. Thomas Adès' Powder Her Face--mordant and musically creative--was presented with a uniformly strong cast in a bold production. I'm very glad I got to see it.