The centerpiece of Friday evening's Carnegie Hall concert was unquestionably Anders Hillborg's The Strand Settings, a song cycle commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for Renée Fleming, and receiving its world premiere. Just as unquestionably, the occasion was an event: the buzz of audience chatter proclaimed eager anticipation in several languages. The performance, in its energy and subtlety, gratified this anticipation not only in the haunting, lapidary lieder, but in surprisingly nuanced and insightful accounts of two repertory staples. The programming of Respighi's Fountains of Rome and the Mussorgsky/Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition alongside Hillborg's work helped me hear each of the familiar works differently.

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Giulio Cesare: Dà pace all'armi!

David McVicar presents Handel's Giulio Cesare as a witty, knowing fable about imperialist projects giving way to cooperation based on mutual respect between individuals and cultures. At least, this is how I read it, and I believe such a reading is supported by the highlighting of Handel's oft-reiterated motif of the conquered conquering. The theatrical exuberance of the production, mingling styles of stagecraft, costume, and choreography from different eras and cultures, is winsome, although I found the comedy occasionally broad for my taste. There is substance as well as style: Caesar gets a veranda of power , and the abundant divans and draperies are definitely modeled on Ingres rather than India itself, let alone Egypt. There is, to be sure, a suggestion of dysfunctional realities under the bright surface. Caesar's military presence steadily grows on the glittering sea, and Sesto is very nearly destroyed by the hollow corruption of the military ethos he embraces in his pursuit of vengeance. Still--a fable this remains, with men and women, the dead and the living, the rulers and ruled, all united in the final tableau. Harry Bicket, with impressive energy and good humor, led the Met orchestra from the podium and the harpsichord. Subtle shifts in tempo and dynamics shifts were used well, I thought, to chart the characters'--and the drama's!--changes in mood. A curious lack of chemistry between the singers subdued the energy of the evening despite accomplished performances, but I found the evening nevertheless enjoyable.

, and the abundant divans and draperies are definitely modeled on Ingres rather than India itself, let alone Egypt. There is, to be sure, a suggestion of dysfunctional realities under the bright surface. Caesar's military presence steadily grows on the glittering sea, and Sesto is very nearly destroyed by the hollow corruption of the military ethos he embraces in his pursuit of vengeance. Still--a fable this remains, with men and women, the dead and the living, the rulers and ruled, all united in the final tableau. Harry Bicket, with impressive energy and good humor, led the Met orchestra from the podium and the harpsichord. Subtle shifts in tempo and dynamics shifts were used well, I thought, to chart the characters'--and the drama's!--changes in mood. A curious lack of chemistry between the singers subdued the energy of the evening despite accomplished performances, but I found the evening nevertheless enjoyable.

Friday, April 12, 2013

Interval Adventures: Visiting Verdi Square

Thanks to Italian-American philanthropy of the early twentieth century, Papa Verdi has a square named after him and a statue in his honor at 72nd Street. Subway commuters and park bench occupants usually seem surprised when I stand still to admire it, but since it's a short walk from the Met, I do so fairly often. As can be seen in the righthand photo above, it is in the grandest tradition of monumental nineteenth-century sculpture. If Verdi were on his plinth surrounded by lyres alone, I'd find it far less interesting... but what gives it its charm, in my opinion, are the figures surrounding Verdi. Grouped around the benevolent master are four of his characters. Whether they seem to be immersed in their own narratives or doing affectionate homage may depend on the angle of light, or one's point of view. The vividness of their expressions makes me hope that the sculptor was an admirer of the composer and his wonderfully human creations. One of the reasons that I keep returning to the sculpture, though, is that I'm still in some doubt about the identity of the statue at the back of Verdi's column; perhaps you, Gentle Readers, can help clarify the matter.

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

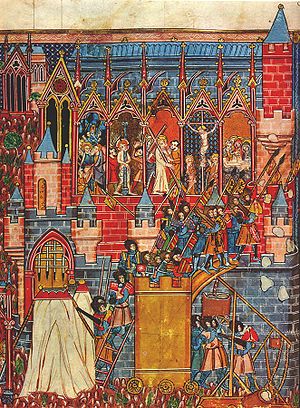

I Lombardi alla prima crociata: o nuovo incanto

|

| The Siege of Jerusalem, 1099 (from a 12th-century chronicle) |

Verdi's fourth opera, written when he was 29 years old, was penned at a time when Meyerbeer's grand operas were beginning to dominate the opera stage, and when resistance to foreign occupation was beginning to dominate Italy's political stage. Both influences are apparent in I Lombardi alla prima crociata, which the composer makes far more interesting and nuanced than Temistocle Solera's libretto, based on an epic poem (!), gives it any right to be. The most striking anachronism of Verdi's opera is its most conspicuous: there was no single word for crusade at the time of the first or indeed the second strange, sweeping, composite movements which would become known by that name (and under that name famously condemned by Steven Runciman as "one long act of intolerance in the name of God, which is the sin against the Holy Ghost.") The libretto for I Lombardi acknowledges the spirit of pilgrimage and the mixed gender of the European hosts; it also, however, claims a mercenary motive which recent historians have noted was implausible in view of the extreme expense and danger involved. Mortgages and wasting fevers were well-known hazards to the Lombard and Frankish hosts, and yet they journeyed to what they called "Christ's land," determined to possess and administer it as faithful vassals of the Lord of Lords. Verdi's music is alert both to the poignancy of pilgrim aspiration, and to the deep tragedy of the perversion of that aspiration into bloodthirstiness. The lovers Oronte and Giselda, often in text he gave them himself, are aware of the contradictions in so-called holy violence: Oronte is convinced of the truth of Giselda's faith because of her own patience and generosity of spirit. In the tremendous finale of the second act, Giselda inverts the cry of the crusaders in screaming against her father's bloodshed: "God does not will this." Michael Fabiano and Angela Meade gave impressive performances in these crucial roles, at the heart of a gratifyingly tight performance from the Opera Orchestra of New York under their respected director Eve Queler.